A Libelium weather station for local measurements.

This is a city-technology project a lot of digital developers we know will embrace because it has the potential to make a difference to our cities and our climate.

The project aims to discover how urban environments affect local, regional, and global climate models. More topically for MESH Cities readers, the project’s scientists ask how can Open Data and Crowd Sourcing strategies help cities better prepare for a century of massive urban growth? In the face of a rapidly changing global climate, these are critical questions for city builders, and Dr. Jason Ching of the University of North Carolina is part of a multinational team offering up a smart way to answer them.

What’s their team’s approach? They are building WUDAPT, short for World Urban Database and Access Portal Tools. WUDAPT’s goal is to quantify the structure and form of the world’s cities on a micro level. Why is that important?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identified the lack of detailed information on urban areas (aka Local Climate Zones) as a shortfall in its comprehensive climate models. In other words, researchers lack critical data on how local conditions in cities affect global climate projections. Getting that data is a big project that needs your help to succeed.

As an experienced researcher and administrator, Dr. Ching understands the magnitude of WUDAPT. He spent a career at the US Environmental Protection Agency and was Chief of the EPA’s atmospheric model development branch for eight years. His colleagues are also well qualified to appreciate how difficult it will be to assemble the fine-grained information needed to satisfy the IPCC’s needs.

Dr. Ching’s colleagues include Dr. Linda See who has a PhD in spatial applications of fuzzy logic from the School of Geography, University of Leeds. Dr. Gerald Mills of University College Dublin, the third team member, specializes in quantifying and mapping the micro climate of cities. Together they came up with the idea of assembling city data in a central repository. WUDAPT was born.

Even with the founders’ abundant talent and experience WUDAPT will succeed or fail depending on the quality of data it collects, analyses, and models. That’s why Open Data and Crowd Sourcing are so important to them.

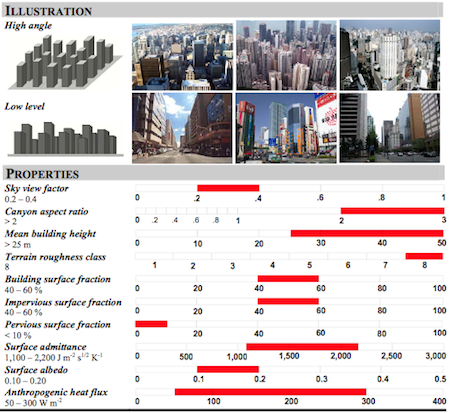

Data from a Local Climate Zone study.

This is where you come in. Imagine mapping a building-by-building database of building material types, heights, micro climate conditions, and ground cover properties for one big city. Now expand that to the thousands of growing cities worldwide. Even if every local and national government would agree to be part of the initiative, it would take years to complete and cost $billions. Here at MESH Cities we think there are other ways to get that information.

First, what if there was a way to hack into Google Maps’ Street Views and using some clever algorithms derive the basic urban dataset WUDAPT requires? While not perfect, the information would be in the order of magnitude needed for key climate projections. Hey “do no harm” Google, now is the time to jump on board. Figuring out how to pull necessary data from your urban panographs would make a big contribution to better climate modelling. It would also be a comparatively small financial commitment. After all, you’ve got the basic information framework in place and a lot of smart people just aching to make a difference. Failing Google’s involvement, can a talented coder or two out there hack up a system that might work?

For those readers who think the information gathered using this technique wouldn’t be accurate enough, we don’t agree. Take a look here at some building energy performance audits being done by Schneider Electric that boost a building’s efficiency dramatically without a lot of building-specific data. Our concept is similar.

Second, in addition to the building information, for WUDAPT to be accurate local meteorological information on a micro level is needed. Again, if we wait for government to do this, well, Miamians will be up to their eyelids in that “nuisance flooding” they’ve been experiencing. Here is where community members can get involved.

Sensor technology and the Internet of Things mashups like those from Libelium offer cheap, effective monitoring tools. An city-specific array of one-hundred or so of these low cost devices (cost=±$200 each) could be deployed and managed by, say, local students. We’d wager that TelCos would be eager to underwrite the cost of the units and pay for the bandwidth needed to network them for the good publicity involved.

In any case, this is a project that needs citizen participation. Why not pitch in an help improve your city, and while you’re at it, the rest of the world too.