(This essay is adapted from the intro story to “Tech in the City” Robert Ouellette wrote for the Winter 2014-2015 of Spacing Magazine)

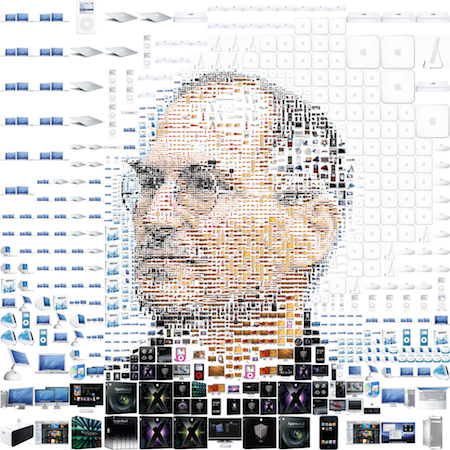

When Steve Jobs built the first mass culture, personal computer in 1976 he envisioned ordinary people as technically empowered as the researchers at IBM or Hewlett Packard. Jobs grew an empire pursuing his vision, living Stuart Brand’s advice from the Last Whole Earth Catalogue: “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” Three Jobsian, digitally-fuelled generations later more than a billion people now carry massively powerful computers in their pockets. Those smart phones, as 1990s AT&T coined them, make once impossibly difficult technical tasks as easy as, well, walking down the street.

And that’s where all those really powerful, mobile computers are. On our streets. It is not surprising then that those streets and the cities they shape are becoming smart too. This year one billion new smart phones will be purchased mostly by consumers. In them is more computing power than all of the personal computers ever made. World changing?

In some ways our cities have always aspired to be smart. Neuroscientists in the United States discovered that modern cities organise themselves in surprisingly familiar ways. They too share brain-like patterns of connectivity. This emergent self-organisation is remarkable in its own right, but when a virtual world of hyper connectivity is layered over our brain-like cities, a new, unexpected level of empowerment evolves. Enter Google Street View, Airbnb, Uber, and a million other possible Apps that collapse the physical and conceptual distance between us.

The history of architecture and city design is, arguably, a catalogue of attempts to capture in physical form the abstract relationships between people and their institutions. Winston Churchill said, “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.” To Churchill, the design of Britain’s Parliament is in a causal relationship with the evolution of British democracy.

If static space can have that much political influence imagine how governments might change in the post Steve Jobs, hyperlinked world. Mashing up our always-with-us smart phones with the so-called Internet of Things promises to do just that. When citizens, infrastructure, politicians, and city administrators connect through two-way communications systems new, hopefully better, forms of governing are going to evolve.

For example, people in smarter, responsive cities will perform the prosaic housekeeping tasks of reporting potholes or broken lights, but they will also contribute to complex decision making including managing traffic patterns in real time or reducing demand for costly lighting, water, and electricity. All that connectivity isn’t restricted to things, it gives people direct access to their politicians via social tools like twitter or facebook or countless other media yet to be invented.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that this new empowerment disrupts — hell, smashes to bits, as it were — old ways of doing things. Strategists thanked then nascent social media for Obama’s 2008 presidential victory over a less digital savvy opponent. That was just the beginning. Digital technology shapes new forms for Churchill’s parliamentary space. While it rewrites the urban code, our policy makers are barely hanging on. Most of them act like they are not ready for the challenge of digitally driven connectivity — they only see its threats to the old order, not its potential for a new one.

Could it be a better time to be a digitally capable architect, urban designer, or city planner who gets the idea of bottom up, emergent design?

Because all this change creates a design vacuum. What should the shape of our connected cities be? What form will our buildings take? How will this emergent technology change our experience of public space, our relationship with different levels of government, our ability to address climate change, or our capacity to address those in need? Who will have the skill and talent to design links between empowering technology and cities meaningful enough that even Jane Jacobs would approve? Jobs’ fourth generation of users will probably find out, but between now and then it will be one hell of a crazy ride. Are you ready citizens?