“Space and light and order. Those are the things that men need just as much as they need bread or a place to sleep.” Le Corbusier

This Is How Cities Evolve

When given new, innovative tools and methods the best designers will imagine ideal or even utopian uses for them. In the process of satisfying some aspirational human need they create new markets others never imagined. And if their solutions, and the complex systems that inspire and support them, could be frozen at that initial moment of conception then the world would be a much different place than it is today—for better or worse.

However, time, and what strategists call product commodification, tend to mutate those idealized solutions into their most easily distributed forms, a process that often debases the original creative purpose. How does that devolution happen? Mass market production and distribution—let’s call them our global productive capacity—are the forces that distribute end products to satisfy market demand. Initially those products remain close to the original ideal but over time that changes.

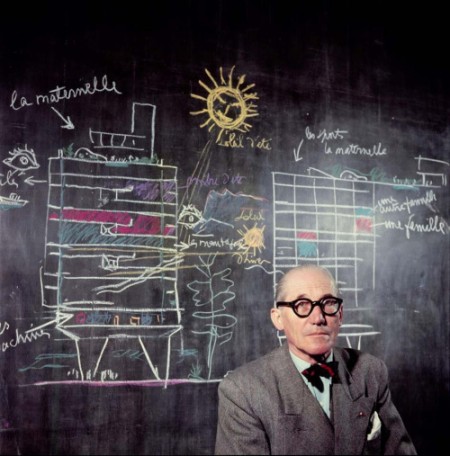

Look, for example, at how the architect Le Corbusier designed high rise living. His initial solutions took the complex social interactions of traditional, horizontal cities and, by embracing new construction methods, fused them into more land and energy efficient vertical forms. Critically, those towers were also desirable places to live because essential services were not just down the block as in typical cities, they were in the block.

The highrise form at the end of things? Mong Kok.

As Corb’s formal solution was distributed, however, it changed. Policymakers and developers saw the high rise residence as a way to house growing populations quickly and cheaply. And that’s what happened. Most high rise developments in the world’s cities have more to do with the type shown above in Mong Kok than they do with Corbusier’s original. Cheap distribution and manufacturing debased the initial, ideal form because the mass market embraced the technical form, but not the generative social vision behind it.

The other great city forming innovation of the 20th Century, the car, follows a similar trajectory. Early designers saw it as a transformative technology to ease the burden of human mobility. Because cars were expensive to build, designers learned to favour a doing-more-with-less approach. Streamlined auto bodies cut aerodynamic resistance allowing the same basic engine and frame configuration to go faster and farther than their non-streamlined competitors.

The A.L.F.A 40/60 HP road car made by Italian car manufacturer A.L.F.A (later to become Alfa Romeo). This model was made between 1913 and 1922. Designed by Giuseppe Merosi.

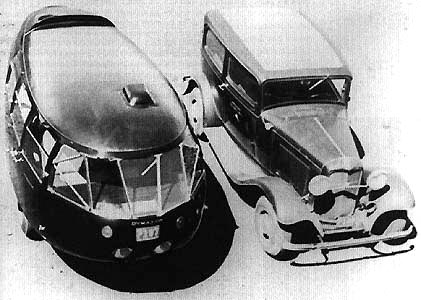

About ten years after the Ford Motor Company brought mass production technology to the car market, efficiency of manufacturing methods superceded performance design efficiency as the key success factor in the automotive industry. Better fuel efficiency as an ideal wasn’t done yet though. In the early 1930’s the American designer/inventor Buckminster Fuller took up the challenge of creating a better automobile typology. His Dymaxion Car reimagined the way automobiles could be built. But it was too late. The car marketplace had embraced mass production over energy efficiency. The embedded capitalisation of then entrenched oil to mobility infrastructure slowed innovation until the end of the century when electric cars finally reemerged as a viable, efficient type.

The 1930’s Dymaxion Car Vs the mass produced car of the era.

Whence The Smart City

The increasing acceleration of technology driven change isn’t limited to the making of things. By the late 20th Century powerful information technologies kick started new ways to conceptualise the future of the world’s cities. The then nascent Internet working hand-in-hand with a massive acceleration in computing power spurred design theorists like MIT’s William Mitchell to see cities dematerialising into “Cities of Bits.” A new kind of idealised design revolution was afoot.

The Emergent City. A Life From Complexity to The City of Bits, By Stanza

According to Mitchell, the core functions of a city from education through to medical care will be transformed. From his “City of Bits” book: “And eventually they will find new ways to accommodate human needs by recombining transformed fragments of traditional building types in a matrix of digital telecommunication systems and reorganised circulation and transportation patterns . . .”

“Networks at these different levels will all have to link up somehow; the body net will be connected to the building net, the building net to the community net and the community net to the global net.” In many ways his predictions about the digital future were correct, but market commodification is changing the way that future is distributed.

I met Mitchell during my time as Director of the Information Technology Design Centre at the University of Toronto. His vision for the future of cities was contageous not to mention influential. By that time he was helping launch MIT’s acclaimed Open Courseware bringing that institution in line with his vision of digitally distributed access to knowledge.

Enter the 21st Century

But Mitchell would look a state-of-the-art of digital cities today with disappointment. The market’s commodification of the urban agora vision is less about making cities better than it is in exploiting big data access to the habits of its inhabitants. And is the Uberisation of everything a city building mechanism or does it continue to lower the bar of what citizens can expect from the formal construct we call cities?

In any case, the digital city a.k.a. the Smart City or the MESH City remains an unfinished project. Like the high rise and the automobile, digital technology is an engine of urban disruption the type of which we’ve never had to manage before. Its form will be commodified by the marketplace. Yet, there is hope that this engine of transformative urban change will produce more solutions like Tesla’s PowerWall than it will better ways to spy on your habits.

And as the cycles of innovation and commodification accelerate in a hyperconnected world, are we ultimately going to arrive at an ideal realisation of the future city at the end of things? As designers we have the power to shape that future. Will we?