Cars to Go when you need them. Why overpay for private auto insurance and loan financing?

Advanced, 21st Century networking solutions are shredding the North American consumer’s aspiration for a car in every garage.

Welcome to the new, MESHed world of digitally connected urban travel. On-demand transit has arrived. Greener cities are just one part of an urban transformation the future promises.

What’s fueling the change from where we’ve been to where we are going?

First, today’s drivers inherited once successful but now obsolete auto industry economies and transit design strategies. Overcrowded highways are slow. Lack of investment in mass transit—a policy favouring entrenched auto sector industries—resulted in more cars on increasingly congested road systems.

What is the end result of this old 20th C. system?

Suburban dwellers are losing the mobility advantage they once enjoyed over their urban friends. With clogged roads now part of everyday life in the outer suburbs, living downtown means shorter commutes for workers. Good urban design is also making the choice between walking fifteen minutes to work or driving to work an easy one.

Which lifestyle would a sensible city user choose? And why on earth would anyone add to the financial burden of car ownership by overpaying insurance companies when on-demand cars are nearby when needed?

Even Canada’s pro-oil, Harper Government lost faith in the old auto sector model. It sold off the remaining shares of bailed out General Motors Co. last week for a multi-billion dollar loss. Why keep them? They will only lose more taxpayer money. Is the sale a symbolic end to the slow motion, environmental disaster that is too many cars in cities?

Maybe.

GM is the poster company of 20th Century rust belt thinking. Its business model has no place in the new world of digitally empowered, smart consumers. Here is why.

GM and other auto industry players started to lose their competitive advantage as long ago as the 1950s. What caused their downward spiral? Too much success. Market dominance led them to believe yearly changes in style were more important than fundamental market innovation.

In other words, they grew complacent. Changing a car’s sheet metal was far easier and profitable than reengineering production facilities, inventing more durable steels, or designing fuel-efficient engines. In fact, under their resources-are-cheap worldview, planned obsolescence was the driver of auto market growth. Buy a car today and toss it in the trash when it rusts out or breaks down or is no longer stylish four years later.

North American automakers became so fat with cash and government perks following that model they didn’t even bother to try and out compete better made Japanese and German imports. That’s part of the reason why those nations took over the American marketplace—in league with India’s evisceration of the auto industry’s co-dependant partner—the American steel sector.

History repeats itself. The same disruptive change is happening again. But this time it is the whole automobile industry rather than a few key players who will feel the pain. The biggest shift in the auto market since Henry Ford embraced the assembly line is here and with disruption comes reinvention.

Again, entrenched auto market players will be caught off guard. In 2014 economists at Morgan Stanley predicted where the automobile sector is going. Their optimistic results call the future of cars an “Autopia.” It turns out that their enthusiasm for more cars was premature.

Here is why.

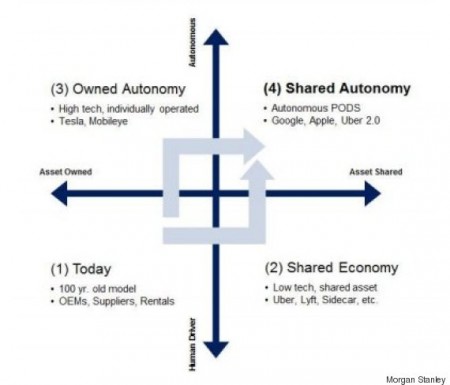

The Autopic future the economists envisioned is embraced in one simple chart.

Hand-in-hand with the sharing economy autonomous cars are the future—Morgan Stanley

As the car market transitions from today’s model to the shared autonomous model (quadrant four), the report’s authors maintain that car use would again increase, leaving behind the flat car sales trend of post 2008. They explain:

We believe autonomous cars can change this trend and boost miles driven significantly. If driving—whether as a work commute or an interstate vacation—is a comfortable, stress- free experience that gives consumers their own private space and flexibility of schedule, with little actual involvement in the driving activity, we believe consumers may be willing to switch away from the inconveniences of public transportation to “driving” their own autonomous vehicles.

Could they be more wrong? MESHed technologies empower citizens in ways that change the game of getting around cities. That, along with a demographic shift, a lagging economy, and improved urban design, result in people embracing the idea they don’t need to be caught up in the auto market treadmill. They have other, better choices.

Call it Uber-izing. Or call it the resource sharing economy. However the information-driven shift is described, one thing is certain: we really don’t want to spend countless hours moving from point A to point B in a car if we don’t have to, even if that car is driving itself.

Better urban transit systems are evolving. So-called Pop Up transit reimagines how mass transit can be efficient as well as comfortable. On-demand car services are maturing too. The service economy may just trump the rust belt economy.

The next ten years will tell. In any case, MESHed cities will be more livable and more sustainable as a result. Automakers, on the other hand . . .