The John Street Toronto virtual city navigation stack circa 1995

Are today’s connected citizens confused by the latest digital city offerings? Probably, if only because any social benefits from the technological hype associated with the promotion of smart cities have yet to be demonstrated in a meaningful way. Sure. People can find the closest place to buy a pizza, but have these new digital tools made a difference to the way we design and govern today’s cities?

Our founder has researched and developed digital city solutions for more than two decades now. Together with some remarkable collaborators, he launched an innovative virtual city tour in partnership with Apple using that company’s then nascent QTVR technology. Of course, it was bleeding edge at the time (1990s). The back-end server technology needed to make digital navigation ubiquitous did not exist. About ten years later Google made it practical. You may have heard about that upstart Internet search company and its commercialization of the searchable urban interface called Google Street View. Navigating the modern, digitally-documented city was a value added service every web user could learn to appreciate because there was a time-saving benefit.

We can’t claim ownership of the virtual street, city navigation paradigm. That honour, as far as we know, goes to MIT and Nicholas Negroponte’s Digital Aspen of the 1970s. And theorists were exploring the idea of using technology to better navigate the city for decades before then. The generative principle behind our early work was that the stuff that makes cities livable could be made visible, or part of the public domain by pulling it out of institutions and bringing it to the street.

We adopted the quote, “The city is a book with 100,000 million poems,” as our mission statement. Our intent was to define the space where poetry meets and informs technology and together they create a virtual city with the nuanced characteristics of a real city.

Given all this theoretical and practical experience gained navigating the emerging digital city, what is the state-of-the-art? The MESH Cities’ view is that the future we imagine is taking far too long to arrive. Part of the problem is, as we’ve argued repeatedly, the city is a living interface device made usable through billions of design choices over millennia. Digital device technology is the young upstart. It wants the keys to the urban kingdom, but the truth is compared to the easy-to-understand, interactive complexity of cities iPhones or Blackberries are kindergarten neophytes. No wonder citizens get lost in the digital city: the tools they have just aren’t up to the task.

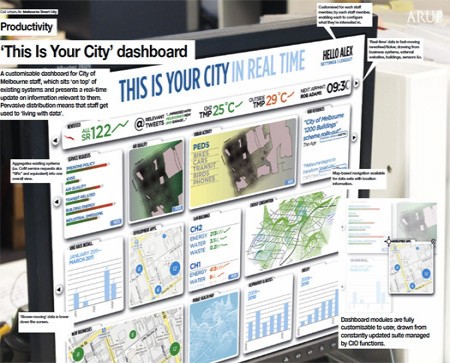

ARUP’s City Dashboard (Melbourne)

Shannon Mattern of the School of Media Studies in New York offers a good overview of recent attempts to develop models of the city as interface. MESH Cities has discussed most of them but not in one posting. In her Design Observer essay titled, “Interfacing Urban Intelligence,” Mattern explores the urban interface using normative, screen-based paradigms. Right now that model is the state-of-the-art given the thousands of digital developers looking to cash in on the information-as-city gold rush. That said, MESHed cities are best served by the next generation urban interface which is spatial/temporal not to mention synaptically driven.

We’ll end this discussion with Mattern’s interface typologies:

- The materiality, scale, location, and orientation of the interface. If it’s a screen: where is it sited, how big is it, is it oriented in landscape or portrait or another mode, does it move, what kinds of viewing practices does it promote? If there is audio: where are the speakers, what is their reach, and what kind of listening practices do they foster?

- The modalities of interaction with the interface. Do we merely look at dynamically presented data? Can we touch the screen and make things happen? Can we speak into the air and expect it to hear us, or do we have to press a button to awaken Siri? Can we gesticulate naturally, or do we have to wear a special glove, or carry a special wand, in order for it to recognize our movements?

- The basic composition of elements on the screen — or in the soundtrack or object — and how they work together across time and space.

- How the interface provides a sense of orientation . How do we understand where we are within the “grand scheme” of the interface — how closely we’re “zoomed in” and how much context the interface is providing — or the landscape or timeframe it’s representing?

- How the interface “frames” its content : how it chunks and segments — via boxes and buttons and borders, both graphic and conceptual — various data streams and activities.

- The modalities of presentation — audio, visual, textual, etc. — the interface affords. What visual, verbal, sonic languages does the interface use to frame content into fundamental categories?

- The data models that undergird the interface’s content and structure our interaction with it: how sliders, dialogue boxes, drop-down menus, and other GUI elements organize content — as a qualitative or quantitative value, as a set of discrete entities or a continuum, as an open field or a set of controlled choices, etc. — and thereby embody an epistemology and a method of interpretation .

- The acts of interpretive translation that take place at the hinges and portals between layers of interfaces: how we use allegories or metaphors — the desktop, the file folder, or even our mental image of the city-as-network — to “translate,” imperfectly, between different layers of the stack.

- To whom the interface speaks, whom it excludes, and how . Who are the intended and actual audiences? How does the underlying database categorize user-types and shape how we understand our social roles and expected behavior? This issue is of particular concern, given the striking lack of racial, gender and socioeconomic diversity in much “smart cities” discourse and development.