Tsunami rolls over Japanese coastline.

When a tsunami swept over parts of north-eastern Japan in 2011 it left a legacy few will forget. In a blink we were reminded just how powerful, not to mention capricious, oceans can be. Images like the one above illustrate that when the thin line between the world of man and the forces of nature is breached even the most capable societies are rendered impotent.

But massive ocean waves were only one force unleashed that fateful day in March. Water pumps in Fukushima's nuclear power plants were disabled by the tsunami's waves. The result was a slow motion catastrophe Japanese officials were powerless to stop. The nuclear cores of three reactors lost essential cooling. Without water keeping radioactive energy in check the inevitable happened: Meltdown.

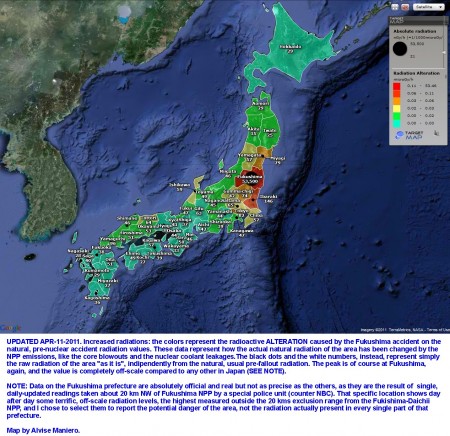

Radiation was released into the atmosphere. Fortunately, the prevailing wind that time of year took most of the airborne radiation out over the ocean. But much found its way inland. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese were evacuated. Many remain homeless today kept off their ancestral lands by the invisible but none-the-less deadly power of nuclear contamination.

Governments and industry can only do so much in situations like this. Resources are scarce. Monitoring equipment is in short supply. Just how much of Japanese soil was contaminated by radiation? Getting accurate information on a fine grain level is difficult. Sharing that information in real time is almost impossible.

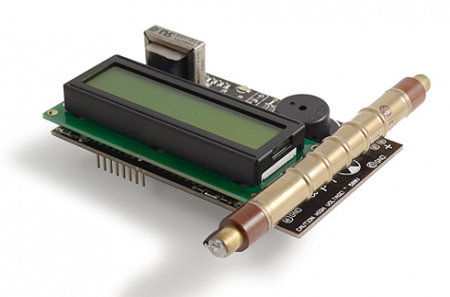

Enter Libelium. One of MESH Cities' favourite Internet of Things developers, Libelium continues to find new applications for its core products. Their researchers thought a mash up between the ubiquitous Arduino platform and Geiger sensing tubes might just supply enough Internet aware devices to make a difference. They were right.

Arduino, meet Geiger sensor.

Here is what Libelium has to say about how their technology is changing things in Japan:

Governments were once the only source of information regarding radiation levels around a nuclear plant or a specific zone within a country. But thanks to a cutting-edge combination of cheap radiation sensors (such as Libelium’s Radiation Sensor Board), crowdfunding and crowd data sharing, some organizations have arisen to share this kind of information with everybody.

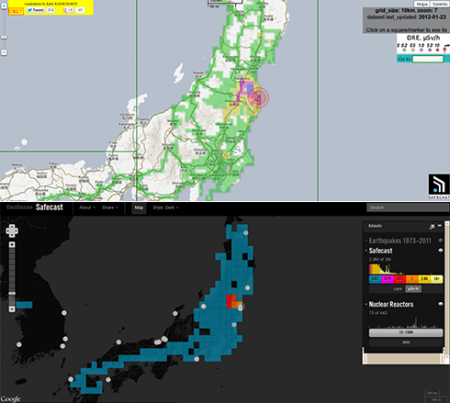

A perfect example is Safecast, a global sensor network for collecting and sharing radiation measurement founded by a small group of people in the U.S. and Japan a couple of days after the Fukushima disaster. They got money from a crowdfunding site and found some allies on the ground at the Keio University in Japan. In just four days, the project was funded by anonymous donors and started to deploy sensors in Japan and show the data on a website.

Safecast’s founders proposed equipping as many people as possible in Japan with inexpensive radiation sensors. Volunteers would send in their findings over the Internet, which would then be displayed as data points on a Google map. The entire project would be open-sourced, and all the data would be made available to anyone who wanted to use it.

The results of the Libelium sensor deployment illustrate just how powerful the ubiquitous computing and crowdsourcing mashup can be.

Real time radiation monitoring across Japan made possible by Libelium.