What happens to city planning when local citizens can work with developers to inform design strategies?

The community group Active 18’s influence on the urban design of its neighbourhood may well represent the future of how cities will be designed. In case you didn’t know, the group represents residents of Ward 18 and the Toronto district known as the “Triangle.” Long considered the nexus of Toronto’s arts community, Queen Street West is a unique place. That’s why when a rash of development activity started residents asked what all this building was going to look like and how would it impact their neighbourhood.

This is not a cliche story about downtrodden residence up against big, bad developers. People in this neighbourhood are smart, media aware, and are part of a well-established social network. Their approach was to ask what can we do to make the proposed developments better.

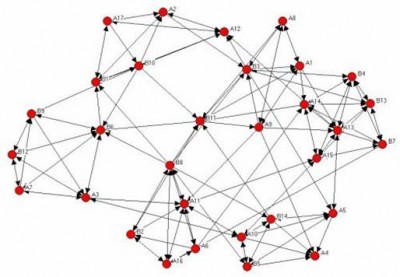

The group gathered together some impressive experts from the design community including artists, architects, urban designers and economists. Meetings and a design charrette – plus hundreds of hours of pro bono work – generated a scheme that is exponentially more considered than a standard, not a lot of time or money to think of the big picture, developer proposal. The city noticed. So did the OMB who asked all the groups involved to work together to come up with a mutually beneficial scheme. Giving other community groups access to urban design best-practices through the Internet, for example, may well change the face of cities one development project at a time.

There is no such thing as bad press in today’s condo market, especially when a star architect is acting as the agent of radical change. Many saw the sales centre as the community equivalent of a Venus flytrap: alluring in a media-centric way, but cloaking disaster for the unwary. Neighbourhood residents were quick to point out the danger. The sales centre sits in a unique Toronto district now reeling from a flurry of developer-led proposals. An artists’ haven for decades, the once-marginal streets of the district offered the perfect blend of low-cost amenities and cheap space. As a result, the old industrial buildings here host a maze of artist studios of all sizes and types.

Artists, as every developer knows, give credibility to neighbourhoods in transition. Streets that seem fragmented and even threatening to people accustomed to the bland sameness of suburban living are, to artists, a wealth of unexpected experiences and untapped potential. Creative people move in. Over time, the streets become safe again. Galleries open. Restaurants fill up. A Starbucks appears. Then developers come. Real estate prices, of course, go up in step with demand. Artists get forced out. Then the cycle starts again.

Now, backed up against the railway tracks, the artists are no longer willing to move. ”We’re not against development at all,” says artist and resident Michelle Gay. ”That’s not the point. We just want a coherent plan.” Why? At least three different developers are vying for zoning adjustments on the land south of Queen and west of Dovercourt. The problem is that no modern zoning plan exists for the area. Developers are in front of the OMB right now arguing against existing four-storey limits on Queen Street.

At stake for the community is a wholesale change to its character. Instead of the two-, three- and four-storey buildings now lining the street, new proposals include buildings as tall as 10 storeys on the south side of Queen. Further south, toward the tracks, 25-storey towers are planned. Through their Active 18 association, Ward 18 residents are working on a development plan they think is right for this community. In fact, Active 18’s ideal vision might well be described as an institutionalization of arts-centred culture in west Toronto — a community designed to be a vibrant incubator for arts but in a way that sustains rather than displaces the very people who lead innovation.

Active 18 assembled some of the city’s brightest artists, architects, economists and planners, and the results are remarkable. Instead of the disjointed clusters of buildings seen in the current OMB applications, a new community full of promise seems within grasp. Their plan makes sense. The streets are rationally laid out. There are attractive parks and well-considered vistas. Ken Greenberg, the urban designer who chaired the community design meeting said, ”One of the most positive outcomes of the process is the community’s desire to help the developers build a sustainable arts presence into their design.” Informed by the community’s results, the city’s urban design department is working on a new plan of its own. It is due in June. Local residents worry that the OMB may well approve developer applications before then. Last Friday, though, the OMB panel suggested that all the parties involved work together for a mutually beneficial plan. Area residents expressed relief.