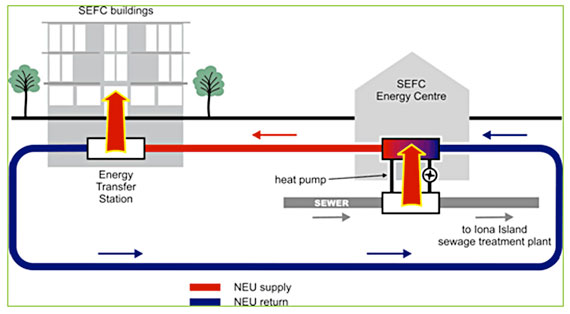

Heat from waste diagram: Vancouver’s False Creek neighbourhood.

Gillian Steward is a former managing editor of the Calgary Herald. gsteward@telus.net The story is used with permission.

CALGARY—Who knew that poop could be used to heat buildings? Or that wind could power a train?

It may sound funny, not to mention far-fetched, but these are more than just wild ideas. They are but two examples of innovative projects in western cities designed to make going green an integral part of urban life.

“There has been a normalization of environmental initiatives in urban areas. . . . Canadians now expect that their cities will consider the environmental and social implications of municipal policy,” states a report recently released by the Canada West Foundation that focuses on innovative green projects, most of them undertaken by municipal governments from Winnipeg to Victoria.

Many western Canadians depend on natural resources such as forests, oil, uranium and hydro to earn a living. And while there is plenty of controversy about the impact of these industries on the environment, municipal governments are not waiting for the dust to settle. They are undertaking all sorts of projects to reduce their carbon footprint and create healthy, sustainable cities.

Here are some of the projects that the CWF listed as the most groundbreaking:

- Vancouver’s Neighbourhood Energy Utility, which is owned and operated by the municipality, is the first utility in North America to capture and use waste heat from untreated sewage. An insulated hot-water pipe system distributes the thermal energy to new buildings in the Southeast False Creek neighbourhood, including the Olympic Village, where it is used for heat and hot water

- Calgary’s light rail transit system was the first public transit system in North America to be fully powered by wind. A group of dedicated windmills in southern Alberta provides the electricity that is then purchased in an offset capacity by Calgary Transit. By the end of this year all the electricity used by Calgary municipal operations will be generated by wind.

- Edmonton has the largest collection of sustainable waste processing facilities in North America. The city’s waste management centre processes residential and commercial recyclables, compostable waste and electronics. It is already diverting 60 per cent of household waste from landfill and expects to divert 90 per cent of its waste from landfill by 2015. A key part of the plan is a plant set to open next year which will convert solid waste into biofuels (ethanol and methanol), a collaboration between the city and private sector that is the first of its kind in the world.

- Saskatoon’s city council established its own development company, which then set about planning and building an environmentally sustainable neighbourhood. Evergreen includes a variety of housing options, efficient use of land, streets aligned so most homes can take advantage of sunshine, LED street lighting and rain gardens. It is now the most popular neighbourhood in Saskatoon.

- In Winnipeg, the Manitoba Hydro building is the first and only large office tower in Canada to receive LEED Platinum certification from the Canada Green Building Council. Since the building opened in 2009, it has proven to be 70-per-cent more energy efficient than a conventional office tower.

These projects were either kick-started or prodded along by local governments. But as the CWF report points out, local governments can’t do it alone; they need the support of citizens. That’s why municipal governments undertook lengthy consultation processes before they moved ahead with long range environmental plans. Calgary’s process, for example, engaged 18,000 citizens.

This urban environmental awareness is making an impact. Last year a report prepared by the Economist magazine ranked Vancouver as the second greenest major city in North America (after San Francisco). In specific categories, Vancouver earned a first place when it came to reducing CO2 emissions, and air quality. Calgary ranked first when it came to water conservation.

The Economist’s report acknowledges that wealthier cities are more likely to undertake new environmental schemes simply because they have the resources to do so. But this is not always the case. Vancouver, for example, is not considered a high-income city compared to many U.S cities and yet it scores high when it comes to environmental initiatives.

The CWF report concludes that cities that have dared to be different are setting the pace. “Success begets success . . . once it was clear that new technology and ideas could result in environmental improvement and financial success, it became considerably easier to replicate and expand on that success.