The information economy’s torrent of endless data is reshaping our culture, its institutions, and its cities. And it is happening fast. When it comes to information technology change is the one constant. So don’t be shocked if the look and feel of your neighbourhood gets a smart city extreme makeover sooner than you expect.

It should be no surprise that smart technologies will influence how we design for the future. But add to that force for change the mutative power of a globally expanding middle class, and you have a collision of influences that is reinventing the look of our cities.

Here is one example.

Stock markets were once fairly stable places (albeit often with a lot of people shouting and throwing paper around). They were part of the urban fabric of any reasonably sized city. Their design was similar to that of banks. Solid. Permanent. Secure. Industrious. They evoked the idea that “Important work was going on inside these granite walls.” We could trust them. The 20th Century. It was easy to add form to function back then.

Flash Crash, 2010

Flash Crash, 2010

The “Flash Crash” of 2010 put an end to the illusion that buildings offered stolid permanence. In seconds Wall Street investors lost billions. Stop losses were useless. We still don’t know what actually happened in those few moments. It had something to do with the overwhelming, instantaneous transactions that skim fractions of a cent off every trade. Super computers that sit right next door to stock exchanges so the speed of light doesn’t slow them down too much—hiccuped.

Welcome to the modern, information city. 21st C cities are process cities. They have to be designed to accommodate functions bracketing quantum mechanics on one hand and getting water to your grandmother’s petunias on the other. Talk about wicked problems. City designers are tasked with absorbing the nuances of all this change while at the same time building environments that accommodate our day-to-day lives.

That’s critical because more than 50% of the people who inhabit the earth now live in cities. Soon that number will reach 70%.

Is there a more important or demanding challenge we face today? Most designers, unfortunately as yet, do not have the breadth of experience not to mention the inclination to deal with the new complexity the densely populated, information-driven city creates.

There are, however, firms who understand that they are designing for complex change they can’t fully predict but they can try to reasonably accommodate.

Rem Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) is one firm that consistently deals with the issues of massively changing cities. One of their projects is Beijing’s China Central Television headquarters.

If you know Beijing at all, you know that the speed of change there is unlike anything the world has seen on this scale before. I first travelled to the city in 2001 then again in 2009. Over those eight intervening years the city had reinvented itself.

At the centre of Beijing’s phenomenal transformation is Koolhaas’s iconic CCTV building (at 550,000 square meters of floor space almost as vast as the Pentagon), a project that some say has killed the era of the skyscraper. Without going into too much theory, the Western world has, in Koolhaas’s view, become stagnant architecturally through its overuse of the ubiquitous skyscraper form first embraced by a then youthful Manhattan. The Rockefeller Center, home to NBC Television, typifies a landmark New York tower.

Beijing’s CCTV building is to 21st C. Beijing what the Rockefeller was to 20th C. New York: A symbol of a dynamic, upstart society intent on defining the future of civilization. Needless to say, Koolhaas’s post skyscraper un-tower was designed around the latest intelligent building systems. If this building is an example, the cities of tomorrow will be smarter, more sustainable, and different looking than the legacy cities we are leaving behind.

While Beijing’s blinding growth spurt is dazzling the international stage, what Canadian design firms take on the challenge of redesigning North America’s aging cities?

One firm is Toronto’s Brown and Storey Architects.

Like Koolhaas, Brown and Storey look beyond obvious stylistic interpretations of design. To them design as a process is not, metaphorically speaking, about making a static photograph it is about editing an interactive movie—an approach well suited to designing for change.

Take as an example the Garrison Creek project. 19th century civil engineering practices buried most of the ravines and creeks that give Toronto is unique character. Brown and Storey revived the covered Garrison Creek by making its figural presence once again part of the city experience. Hydrologic systems that shaped the city’s landscape are made visible.

It is this “embracing of systems” approach to design that gives Brown and Storey’s work its relevance in the smart, process city.

The intersection of Yonge and Dundas Streets is Toronto’s Times Square. B+S took a once dingy commercial block and turned it into a robust, often exhilarating event space that manages to mediate the ongoing stories of urban Toronto. It is designed to accommodate change, but function is also critical to its success. Like Beijing’s CCTV building, Dundas square is a media space. It is a performance space. It is a node on the subway and streetcar system. It also includes an underground, revenue generating, parking lot. Most of all for the public, on those oppressively hot summer days it is a cooling, urban oasis. What smart city want-to-be could do without this kind of popular urban centre? Brown and Storey make the design complexity look easy.

It isn’t.

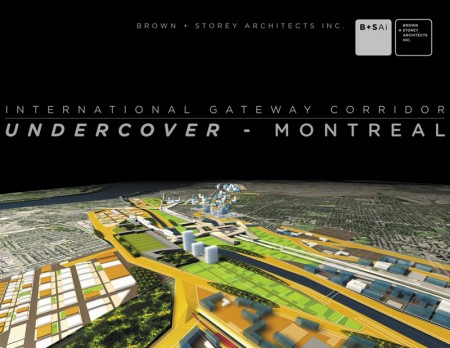

They do grand scale master plans for the modern metropolis too. Note their recent international award for Montreal’s Gateway Corridor as an example. The project considered inventive, new ways to connect Montreal’s airport to the city’s core.

Take a look at the project. It is complex and well considered. It is also beautiful. Importantly for a 21st C city, it provides an ordering system for coherent growth that is also permeable enough to allow for the information-driven, urban improvisations that make for responsive cities.

This is almost impossibly hard to do well. Designing for information-driven change is a demanding art and science still in its infancy. In fact, one of the challenges of creating the smart, responsive cities of the future is empowering the people who will design them. What skills will they need? What social institutions will be there to support them? What companies will help them benefit from the opportunities change creates?

Answering those questions will shape our world.