MESH Cities are places where change happens at the speed of light. Seriously.

With billions of bits of information now influencing the physical reality of our cities, the one constant is change. And it happens fast.

Want proof? Stock markets, for example, were once fairly stable places (albeit with a lot of people shouting and throwing paper around). They were part of the urban fabric of any reasonably sized city. Their design was on par with that of banks. Solid. Permanent. Secure. They evoked the idea that “Important work was going on inside these granite walls.” We could trust them. Ah, the 20th C. It was easy to add form to function back then.

Flash Crash, 2010

Today, however, not so much. The “Flash Crash” of 2010 put an end to that illusion of permanence. In seconds investors lost billions. Stop losses were useless. We still don’t know what actually happened. It had something to do with the massive, instantaneous transactions that skim fractions of a cent off every trade. The super computers that sit right next door to stock exchanges so the speed of light doesn’t slow them down too much—hiccupped.

People lost their life’s savings. In seven seconds.

Welcome to the modern, information city. 21st C cities are process cities. They have to be designed to accommodate functions bracketing quantum mechanics on one end and getting water to your grandmother’s petunias on the other. Who the hell has the nuanced command of design to manage encapsulating that range? Truth is . . . no one.

There are, however, design firms who understand that they are designing for a calculus of moments they can’t fully predict but they can try to reasonably accommodate.

One such firm is Brown and Storey Architects.

James Brown and Kim Storey are colleagues and our respect for them makes us less than objective reporters. Still, their corpus of work speaks for itself. If someone asked us who we’d get to stage manage the design of a MESH City, they’d be on the team. Let us explain why.

James and Kim look beyond obvious stylistic interpretations of design. To them design is not a photograph in a slick magazine, it is an interactive movie. They approach design challenges by studying the ongoing forces underneath the surface. Often, QUITE LITERALLY. This approach is critical when designing for change.

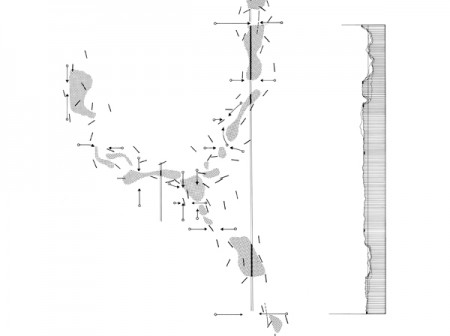

An example is their Garrison Creek project. 19th century civil engineering practices buried most of Toronto’s ravines and creeks. Brown and Storey revived one of them—at least conceptually—by making its figural presence once again part of the city experience. Hydrologic systems that shaped the early urban landscape are remembered in this project by mapping them to the surface.

It is this “embracing of systems” approach to design that gives Kim and James’ work its relevance in the process city.

Dundas Square by day, Toronto

Dundas Square at night (photo by maxxime)

The intersection of Yonge and Dundas Streets is Toronto’s Times Square. B+S took a once dingy commercial block and turned it into a robust, often exhilarating event space that manages to tell the ongoing stories of Toronto. It was designed to accommodate change, but function is also critical to its success. Dundas square is a media space. It is a performance space. It is a node on the subway and streetcar system. It also includes an underground, revenue-generating, parking lot. Most of all for the public, on those miasmic summer days, it is an urban oasis. What MESH Cities want-to-be could do without this kind of popular urban centre? B+S make the design complexity look easy.

It isn’t.

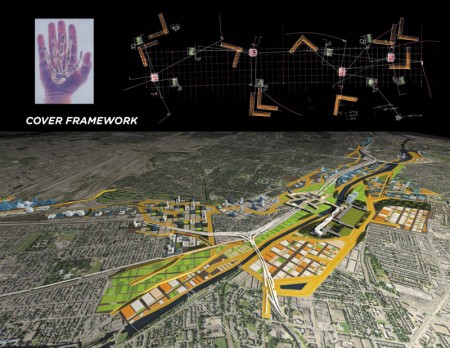

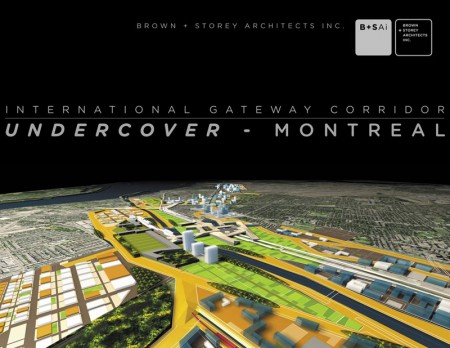

They do grand scale master plans for the modern metropolis too. Note their recent international win for Montreal’s Gateway Corridor as an example. The project offers ways to connect Montreal’s airport to the city’s core.

Is it hyperbolic to say that not since the Haussmann’s Paris or L’Enfant’s Washington has an overarching urban scheme done more to tie together disparate parts of a large, growing metropolis while capturing the zeitgeist of its age? Maybe, but take a look at the project. It is complex and well considered. It is also beautiful. Importantly for a MESH City, it provides an ordering system for coherent growth that is also permeable enough to allow for the urban improvisations that make for responsive cities.

This is impossibly hard to do well. Designing for change is a demanding art and science. Yet these projects show big organizations tasked with building so-called smart cities how it is done.

(PS, In case you wondered, MESH Cities is happy to consult on what it takes to integrate smart infrastructure with smart design. Give us a ping and we’ll explain how)