MESH Cities founder Robert Ouellette learned first-hand about the practical evolution of intelligent cities while studying the rollout of mesh networks in complex urban environments. Some massive but less developed cities (like Beijing) were without a modern copper communications infrastructure. So they decided to go mesh wireless instead. Good idea. Why drag all those copper atoms around at great expense when you can just go digital and leapfrog the competition?

This exposure illustrated how well-entrenched market players–in this case Western cities–with established infrastructure find themselves at a competitive disadvantage when disruptive, technological change tips the scales towards less-developed underdogs.

Those underdogs are countries and cities once considered third world. Because they faced, for example, water shortages, or no communications infrastructure, or informal transit systems they had to reinvent themselves to survive in global, modern economies. And many have. In fact, due to ubiquitous computing and modern logistics systems, they are surpassing their former masters in the deployment of next-generation urban solutions while entrenched infrastructure economies remain lost in 20th C. ideas (Toronto’s on-again, off-again transit planning illustrates how entrenched systems and the public that supports them tend not to change until catastrophe or an Olympics nod forces new spending).

The phenomenon is not new. Over the years it has become apparent that necessity is indeed the mother of invention, or, at least, innovation when it comes to improving cities. We all know the story of London’s investment in a modern sewer system being driven by a series of cholera outbreaks. MESH Cities are no different, except the motivation is not only public well-being, it is now economic prosperity; it makes economic sense to be a modern, sustainable, information city.

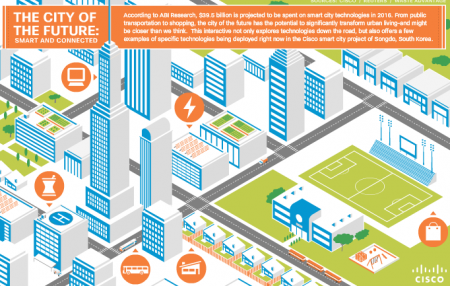

Digital infrastructure giant Cisco has a useful graphic to illustrate some, not all, the elements of a MESH City (they probably quite rightly leave out the innovative power of a mesh-networked public as being outside a typical corporate mission). This graphic relates to systems being deployed in the entirely new city of Songdo, South Korea.

Their six “smart and connected” city functions are:

- The Office

- Well-being

- Energy

- Transportation

- Home

- Shopping and Entertainment

IBM too is reinventing the future of cities with its massive computing capabilities. It has teamed up with Rio de Janeiro to build a “mission control” system that is changing how the city is managed on a day-to-day basis. New York Times writer Natahs Singer offers:

City employees in white jumpsuits work quietly in front of a giant wall of screens — a sort of virtual Rio, rendered in real time. Video streams in from subway stations and major intersections. A sophisticated weather program predicts rainfall across the city. A map glows with the locations of car accidents, power failures and other problems.

The order and precision seem out of place in this easygoing Brazilian city, which on this February day was preparing for the controlled chaos that is Carnaval. But what is happening here reflects a bold and potentially lucrative experiment that could shape the future of cities around the world.

Rio is a city of extremes. Its complex management, infrastructure, and social systems are a snapshot of a city with elements spanning from medieval Europe to 21st Century risk-mitigation algorithms. City managers needed a way to understand that complexity. IBM offered one solution.

Need drives change. Water-constrained cities in North America are embracing new MESH technologies in their effort to survive in the face of dwindling natural resources.

Orange Country California–the home of Disneyland–is one such location. Faced with drought conditions and increased demand for water, Orange county decided it had to turn waste water into drinking water. Steve Gorman of Reuters writes:

The plant takes pre-treated sewer water that otherwise would be discharged to the ocean and runs it through a three-step cleansing process essentially the same technology used to purify baby food and bottled water.

Thousands of microfilters, hollow fibers covered in holes one-three-hundredth the width of a human hair, strain out suspended solids, bacteria and other materials.

The water then passes to a reverse osmosis system, where it is forced through semi-permeable membranes that filter out smaller contaminants, including salts, viruses and pesticides. Reverse osmosis also is the main process used in desalination.

Finally, the water is disinfected with a mix of ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide.

The resulting product exceeds all U.S. drinking standards but gets additional filtration when it is allowed to percolate back into the ground to replenish the aquifer.

These are just a few examples of cities using information systems to plan and build sustainable, livable futures. Is your city part of that change or is it waiting for change to be forced upon it?